The curtain rises. The theater represents a theater.

THE EPILOGUE comes forward.

EPILOGUE: Now, [ladies and] gentlemen, how did you like our play?

—Ludwig Tieck, The Topsy-Turvey World (1798)

Towards a system that desires to become another system

It all starts with the unpredictability of a single day in mid-December. As people walk down 18th street in Gowanus, rain pours from the sky. Gradually, the water drops swell and grow stronger, the wind that carries them becoming more fierce and furious. A mailman, a delivery boy, and a random passerby find themselves squeezed under a nearby deli’s awning, all dripping wet. At this point, the rain has taken over and people have almost completely cleared from the street. It starts slamming into windshields, bubbling in the gutter, washing down leftover plastic bags, cigarettes, receipts; lifting up leaves and undefined detritus. Everything seems to have stopped. No work will be done today, or at least in the next few hours until the rainfall wanes. The mailman gives up on delivering the mail to number 64 and the following apartments on his route; the delivery guy calls in to say that it’s unsafe to drive now, and I am standing under the awning, smoking a moist cigarette and looking at the flowing dramaturgy of currents and objects. A new system, consolidated from the environment, the atmospheric conditions, the productive cycle, and the human factor.

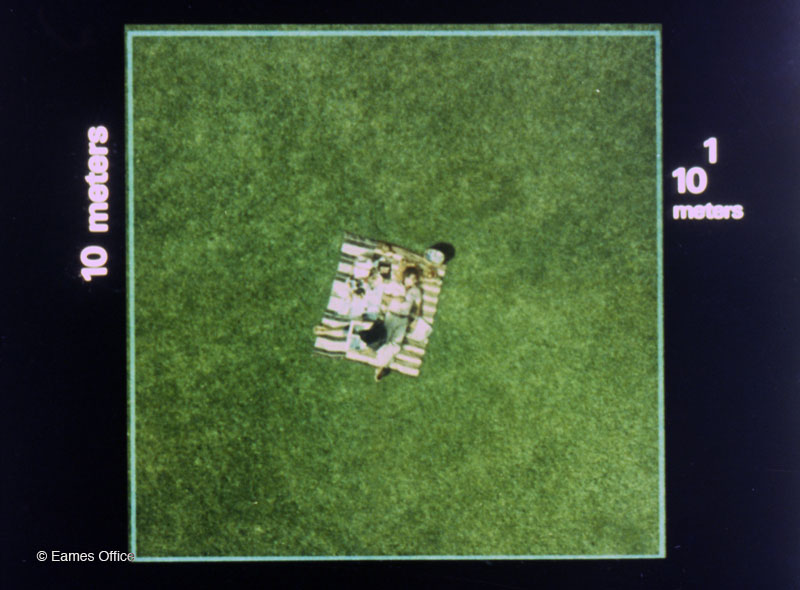

Charles and Ray Eames, Powers of Ten, 1977. Courtesy Eames Office.

It is a situation where one system gets hijacked by another system that is much different in terms of its size, trajectory, state of consciousness, complexity, and motivation. The way the dominant system transmits its desires might be intentional, rational, logical, habitual, or intuitive, unpredictable, atypical, and anomalous. On a microscopic level, between the human and the weather, one obvious similarity emerges. Both are built out of similar particles: oxygen and hydrogen, orchestrated in molecules we know as water, along with some pollutants, minerals, and microorganisms. In the case of rain, those molecules might sometimes integrate acidic pollutants from the air and contaminate the soil, in turn producing bad crops that might cause disease. Apart from their immediate impact on agriculture and healthcare, the circulation of those molecules significantly affects global flows of commerce, finance, transportation, the construction and infrastructure industries, safety, tourism, food distribution, and military operations. Similar molecules make up 70 percent of the human organism: the tepid cocktail of hormones, chemical ions, and electrical impulses that make one feel, think, and act.

In the following paragraphs, I will use few experiments, narratives and works to think how those connections amidst systems are established, and what type of relationships emerge between micro and macroscopic structures.

Jesper Jargil, still from De Udstillede (The Exhibited), 2000. Courtesy Jesper Jargil Films.

Human weather

In the entrance of the Kunstforeningen, Denmark a live video feed shows an anthill located in the desert somewhere near Los Alamos, New Mexico. A thinly drawn grid delineates squares within the projected image. A close-up footage of the hill, like one of the scenes from Saul Bass’s film Phase IV (1974), is transmitted via satellite to the museum space for two months. It follows the ants climbing on the collapsing soil. They are carrying pebbles and food, laboring, running hectically, resting, or resonating within their environment.

There is some sort of order in the ants’ movement that is being tracked. The order, in this case, is expressed through the filmic framing of the operations that construct a window into life-as-is. The grid, superimposed on the image of the nest, corresponds to the architectural structure of the 19 rooms at Kunstforeningen, Denmark. The intensity and complexity of movements of this external, distant, non-human force directs the moods of 53 actors, cast by Lars Von Trier for his durational performance-cum-theatrical experiment in “psychosocial aesthetics” called Psychomobile #1: The World Clock (1996).1

Jesper Jargil, still from De Udstillede (The Exhibited), 2000. Courtesy Jesper Jargil Films. One of the rare documents of Lars Von Trier’s Psychomobile #1: The World Clock is Jargil’s “making-of” documentary. As another interpretation in this mechanism of translations, it focuses on the way in which problems between the actors in real life affected their performance, and vice versa.

Two years prior to Psychomobile, Von Trier started developing the manual for the two-month-long experimental performance that would occupy all four floors and the outdoor courtyard of this museum. Three documents, written with the help of a film scriptwriter, would establish the structure of the project: Document 1 lists the age, gender, character traits, dreams, and possessions of each of the 53 actors, as well as the physical characteristics of the 19 rooms in the museum. Document 2 outlines “Rules and Guidelines for the World Clock,” while Document 3 explained “The Logic of the World Clock and its Placement in Kunstforeningen.” The slice of the outside world, an intentionally heterogeneous cast of 53 characters, would inhabit 19 distinctly designed rooms in the museum. Each room had a title, such as “The Terminal,” “The Archive,” and “The Hippodrome.” There was no plot or script, only guidelines provided by the three documents. The changing conditions of the remote ants’ nest, transmitted through a satellite, would affect the colors of four lights installed in each room. Blinking from red to blue, or passing from green to yellow, the transition and intensity of light would indicate a change of mood for the character inhabiting the space. Each of the actors, assigned to perform the traits outlined in Document 1, would interpret how the change of mood should translate into shifts in the character’s behavior.

There was no planned action, but a continuous circulation of emergence and structure, chaos and control. Through the interaction of discrete actors, complex sets of fluid behaviors overrun each other, or merge, evolve, and transpire. The cacophony of triggered moods emphasizes the layering of interactions, and the directions prompting them become gentle yet persuasive “ecological ‘nudges’”, rather than direct controls.2 The alternating moods act as a kind of “human weather”, with comparable sets of consequences. In this storm, the transmutations and translations from one system to another cause unpredictable effects. 3

At one moment, the video feed of the ants’ nest shows a potato chip being thrown inside, causing a feeding frenzy among the population. The corresponding performances within the rooms of the museum start to change frantically. Another moment within the live video feed presents many of the ants dying from an unexplained cause, prompting a solemn feeling of amnesia amongst the survivors, and causing perpetual silence between the actors. Like any heterogeneous structure, the piece is also generative. The evolving narrative becomes confused with reality: actors who are interpreting a shift in mood by “falling in love” with another actor begin to fall in love with each other in reality. Another actor who plays out the changing lighting as a “nervous breakdown” is not able to distinguish it from a real life crisis. Some of the characters start improvising: after dying in the play, they are resurrected and decide to come back as ghosts. The ants’ nest becomes an uncontrollably powerful system that translates into an evocation of human dramaturgy. The smallest change in the initial conditions of the nest will result in a severe divergence in the final course of the larger structure. This echoes what Edward Lorenz refers to as the “Butterfly Effect,” described as a “sensitive dependence on initial conditions” in his seminal paper “Deterministic Nonperiodic Flow” in which he explains how a minor change in one state of a deterministic nonlinear system can result in quite large differences in a later state.4 In Von Trier’s The World Clock, relationships between human and non-human systems are addressed in real time. Though a shift in scale, one self-contained system is reflected in another. The newly established relationship does not prioritize one over the other, but treats them as systems occurring simultaneously. There is a constant oscillation in focus between a macroscopic and microscopic view of the picture, and the ‘clock’ of one system choreographs the ticking of the other.

INTERMISSION.

For want of a nail the shoe was lost.

For want of a shoe the horse was lost.

For want of a horse the rider was lost.

For want of a rider the message was lost.

For want of a message the battle was lost.

For want of a battle the kingdom was lost.

And all for the want of a horseshoe nail.5

INTERMISSION ENDS. Lights start flickering.

In Félix Guattari’s book The Three Ecologies (2000), three different ecologies become the arenas of the happening: the self, the socius, and the environment, with each ecology fluidly asserting control over the other. One thinks of Michel Serres’s “quasi-object” which devours its objecthood almost entirely in order to be able to circulate faster: an impulse of the fiery ball being thrown between the players, metamorphosing through every kick. The impulse acts as “a subject of circulation, the players are only the stations and relays.” 6 Each station this ball passes through will be changed by its passage, becoming the collective, and, if it stops, becoming the individual.

Cover image for DVD of William Greaves’s Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968), published by Criterion Collection. “Heisenberg asserts that we’ll never really know the basis of the cosmos, because the means of perceiving alters the reality it observes. The electron microscope sends out a beam of electrons that knocks the electrons of the atoms being observed out of their orbits. I began to think of the movie camera as an analogue to the microscope….” William Greaves, in Scott MacDonald (ed), A Critical Cinema 3: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers, (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1942).

The construct of the clock organizes our days into more productive, measurable sequences, effectively organizing chaos into discrete systems. Minutes turn into emails being sent out, seconds into products being polished to a glossy finish. Everything can be measured, objectivized, streamlined. If the man-made clock allows us to make sense of chaotic real-time systems, then what does an analogue, biological, and unruly clock such as the ants’ nest express? The ticking of this clock is not unlike the pulsing of the circulatory or nervous system inside an organism, where different chaotic compositions play inside of circadian rhythms, releasing oxygen and dopamine to speed the body up, or converting serotonin into melatonin in order to slow it down into resting phase. Inside The World Clock’s world, the human and non-human agents and networked communications share a “nervous system in the chaotic ecological sense.”7

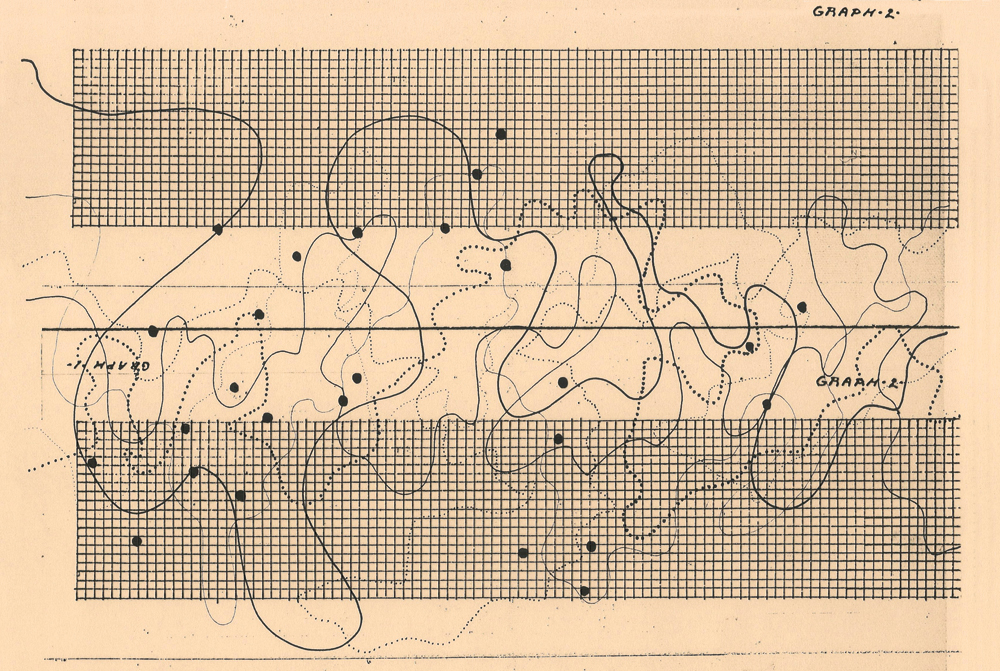

John Cage, Fontana Mix, (1981). Courtesy the John Cage Trust. Cage described the score of Fontana Mix as “a camera from which anyone can take a photograph.”

Unpredictable Orchestra

A structure is like a piece of furniture, whereas a process is like the weather. In the case of a table, the beginning and end of the whole and each of its parts are known. In the case of weather, though we notice changes in it, we have no clear knowledge of its beginning or ending. At a given moment, we are where we are. The now moment.8

John Cage often said that he wanted his music to be like the weather—unpredictable, omni-directional, impermanent, and always changing—allowing the complex systems to appear parallel to the conditions of our daily life. He would “give (himself) over to the weather,” allowing a chaotic variable to determine the directions.9 Cage’s original understanding of sounds and environments comes through his experience inside the anechoic chamber at Harvard: a supposedly silent room devoid of sound, where instead he heard two sounds, one low frequency and one high. The engineer informed him that it was the sounds of his blood flow (low) and central nervous system (high) that he heard, or rather felt, and absorbed from the room, as if the room was informing him of his own being.

On July 14, 1992, between 7:30PM and 9PM, Cage’s composition One was to be performed outside. In the event of inclement weather, it was simply to be cancelled. The atmospheric system of the Sculpture Garden of the Museum of Modern Art, apart from the humidity, wind and temperature, consisted also of layers of urban weather: insurgent traffic sounds, sirens, airplane motors, bird arias, the light chatter of the crowd, and the surrounding hum of the pulsing mist. In Cage’s composition, weather is used as the “medium in which this concert took place, but also its form”.10 It was positioned at the intersections of “whether’s weather”: chance and choice versus concrete variables. The possibility of rain canceling out the music (and performing itself instead) contributed to a system in which the focus is displaced from structure towards process, and from music as an object with definitive boundaries towards a form without beginning, middle, or end. Also, surrendering of control made possible for another structure to emerge, for the “background” to become the “foreground,” and for the invisible metronome, or a ‘clock’, to initiate a new tempo.

Alvin Lucier, Graphic Score for Music for the Solo Performer. Image courtesy of Alvin Lucier, 1965. “Sitting on a chair, eyes closed, Lucier’s brainwaves were recorded from his scalp, amplified and channelled to numerous loudspeakers scattered around the room. […] the loudspeakers were put ‘right up against’ various percussion instruments, which were then activated by means of vibration.” D. Kahn, in Earth Sound Earth Signal: Energies and Earth Magnitude in the Arts (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2013).

In the spectrum of systems, the use of chaos as a variable built into the initial system, may become an organizational principle, or order, for another system to which it is applied. Roboticist Rodney Brooks, one of the researchers into Artificial Intelligence at the MIT Laboratory, has claimed that “the world is its own best model” for action, rather than internal representations or symbolic reason.11 This is what Cage calls “the now moment”: the world is always up-to-date with itself, and has no need of a model or representation. Real-time reaction allows for the system to learn and evolve, as per Brooks’ further claim that, in designing Artificial Intelligence, the system doesn’t have to be built to be “intelligent,” but can use its environment as both a continuous backup and a catalyst.

Nicholas Negroponte with Architecture Group Machine MIT, SEEK (1970). Originally shown at the exhibition “Software,” curated by Jack Burnham for the Jewish Museum in New York, 1970. “SEEK’s stated purpose was to play up the misalignment between the computer’s memory, its programmed functions, and its physical environment. It demonstrated the discrepancy between machine models and the real world. The model failed for many reasons, and not just because it was a blocks world. Most strikingly, by anecdotal accounts, SEEK tended to kill the gerbils.” Molly Wright Steenson, “Microworld and Mesoscale,” in interactions 22:4 (July–August 2015), 58–60.

According to ecologist Ramon Margalef, boundaries between systems in nature are usually asymmetrical, causing more organized systems to always gain information and energy from less organized ones. This applies to the “relationships between plants and animals, atmosphere and sea, environment and thermostat, enzyme and RNA molecule, biotope and community, prey and predator, agrarian communities and industrial societies,” with the second one always feeding on the energy surplus of the other. The parasite dynamics between the systems are embedded in nature. The introduction of this type of parasite, especially into a living system, will upset a previously closed equilibrium, causing it to deviate from its norm. It will cause a system to change and differentiate, as a result of which a different notion of time will pertain from the one that existed in the steady state. From Serres’s perspective, what we call history begins with differentiation and divergence: “the introduction of a parasite into a system is equivalent to the introduction of noise […] [T]ime does not begin without its intervention”.12

Silvia Maglioni and Graeme Thomson, still image from the video In Search of UIQ, (2013). Image courtesy the artist. After translating Guattari’s script “A Love of UIQ,” the authors used the form of a visual essay to extend the idea of the film as a process of contamination, in which the initial screenplay acts as a cinebacteriological vector.

… And the Relative Size of Things In the Universe

Real-time infiltrates and parasitizes each one of three versions of Felix Guattari’s script for a science-fiction film A Love of UIQ (1987). It took seven years and three versions to complete the screenplay, which Guattari began writing in 1980, and even so, it would never be made into a film. Even the screenplays had to wait until 2012 to be recovered from the archives and published as a book. As Guattari states in the “Principal Objectives and Themes” that precede his screenplay, “Everything could be rewritten—since with each new reading its statements are modified, the meaning of clauses shifts.”13

In a way, the script acts as a strange quasi-object, mirroring the prevailing sociopolitical situation of the time, and lends itself to further transmutations. Each one of the three versions acts like a barometer, and according to each, time, place, and characters shift in consonance with the most urgent events. Recounted through flashbacks and scrambled memories, they switch from a commune somewhere in the eastern US in the first version, through the second version which takes place in the control society of Tativille-style complex in France in the near future, to the third version, a present-tense tracking of molecular, collective practices in the squat culture of 1980s Germany, in which the specific cultural context pertains to the realms of contagion and contamination. The proposed narrative arc follows UIQ from the title, or “Univers Infra-Quark”’s misadventures in seeking visible human (and cinematic) form, through various states of parasitizing, transmitting, embodying, and becoming (child, woman, animal, multiple).

Like the camera descending from the sky onto a picnic scene in Charles and Ray Eames’s “Powers of Ten,” and zooming in into the hand of a sleeping man all the way to the carbon atom, the script connects the infinitely small (UIQ) with the whole range of the known universe. UIQ presents itself as a potential force, a non-human intelligence existing in the infinitely small subatomic realm that tries to embody itself through various becomings. At the beginning, the main character Alex, a biologist, establishes communication with UIQ through a chloroplast in a strain of a phytoplankton acting as a relay. From that initial contact, UIQ will speak and exist through polyphony of machines, bodies, and voices, unbounding the choreography of forms, micro and macro-events, and transductions. Throughout the script, in trying to find a form for its being, UIQ uses various forms of contamination, transmission, and transduction. It parasitizes and emits its signal through the broadcasting of global communications networks, regroups its form through bird populations and clouds, unleashes a plague, affects and contaminates humans in contact with it, and finally settles itself within an immortal body. In the end, it exists everywhere. All of the known systems it permeates lend themselves to the further forming of complex nervous networks between the microscopic and the macroscopic universes. Through this formation, UIQ tries to simultaneously become “a clock” to the nervous system that it connects to. The infinitely small, constituent particles of UIQ manage to collectively mobilize and merge with the infinitely large - or, could it be that they are from the beginning the same thing, built out of the same molecules, just perceived on a different scale and with different wiring? The Eames’ film ‘Powers of Ten’ uses a similar method, letting the camera zoom out far enough, but also come extremely close to the same subject, that at the final scenes of the exponential enlargement and contraction we end up looking at what appears to be almost the same substance - the flickering lights of protons in atoms constituting a body, or the lights of the stars forming a galaxy.

Bio

Dora Budor (b. 1984 in Croatia) lives and works in New York. Recently Budor took part in institutional group exhibitions “Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art, 1905–2016” at The Whitney Museum of American Art (New York), “Streams of Warm Impermanence” at David Roberts Art Foundation (London), “9th Berlin Biennial” at KW (Berlin), “Fade In: Int. Art Gallery - Day”, Swiss Institute (New York), “Inhuman” at Museum Fridericianum (Kassel), and “DIDING – An Interior That Remains an Exterior?” at Halle für Kunst & Medien (Graz). Her selected solo exhibitions include Swiss Institute (New York), Ramiken Crucible (New York), and New Galerie (Paris). Budor was awarded Rema Hort Emerging Art Grant in 2014, and has participated in panel discussions at Judd Foundation, Art Basel Miami Salon and Whitney Museum of American Art. Her forthcoming activities include group exhibitions at Palais de Tokyo, (Paris, France), K11 Art Museum (Shanghai, China), Vienna Biennale (Vienna, Austria), and new commissions for Frieze Projects and open air exhibition on the High Line (both in New York).

- Lillemose, Jacob. “Lars von Trier’s Psychosocial Aesthetics”, Frieze blog, posted 04/09/14, accessed http://frieze74.rssing.com/chan-5625831/all_p11.html ↩

- Murphie, Andrew Murphie. “The World as Clock: The Network Society and Experimental Ecologies,”, Topia 11: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies, 11, (Spring 2004), p117-–139, 2004. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Edward N. Lorenz, “Deterministic Nonperiodic Flow,” Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 20:2 (1963). ↩

- Benjamin Franklin, “Poor Richard’s Almanack” (Waterloo, IA: USC Publishing Co., 1732). ↩

- Michel Serres, The Parasite (Minneapolis: University Of Minnesota Press, 2007), 224–34. ↩

- Taussig, Michael. “The Nervous System”. New York: Routledge, 1992. ↩

- Joan Retallack, The Poethical Wagner (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2003). ↩

- John Cage, “The Future of Music,” in Empty Words (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1979), 178. ↩

- Rodney A Brooks, “Elephants Don’t Play Chess”, Robotics and Autonomous Systems 6:1–2 (1990), 3–15. ↩

- Jack Burnham, “Real Time Systems”, Artforum, September 1969. ↩

- Michel Serres, The Parasite, University Of Minnesota Press, 2007 ↩

- Félix Guattari, A Love of UIQ (Minneapolis: Univocal Publishing, 2012). ↩