The following is an English translation of curator Tamara Díaz Bringas’s 2017 essay “If Water Didn’t Drown a River.”

Starting with the exhibition “James Bay Project, A River Drowned by Water” (SFMOMA, 1981), the essay is a case study of the practice and methodology of Nicaraguan artist and curator Rolando Castellón. Although Castellón is celebrated for his significant contributions to artistic contexts in Central America, his work in the United States from 1956 to 1992 is not established within a larger discourse of contemporary art or art history. Here, Díaz Bringas highlights a powerful precedent for the kind of political-activist research exhibition so common today and reintroduces Castellón to an English-speaking public as an innovative figure who operates between the Nicaraguan, Costa Rican, and US artworlds.

—

“James Bay Project, A River Drowned by Water” was a traveling exhibition by the German artist Rainer Wittenborn and writer Claus Biegert about a dam that flooded Indigenous territory in Northern Quebec, Canada. The exhibition included installations and a selection of drawings, paintings, photographs, maps, artifacts, and found material collected during the duo’s three-month research trip to the region, accompanied by essays by anthropologists and art historians as well as interviews with local residents. With support from the Goethe-Institut, the project was exhibited at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art between May and July 1981, which also marked the last exhibition that Rolando Castellón Alegría curated at the institution. My proposal here is to consider the Nicaraguan artist and curator’s practice through a specific focus on documents and gestures from the “James Bay Project” exhibition.

If we were to enter the galleries of SFMOMA in the spring of 1981—as we can today, through photo documentation found in the archive—we would see two monitors, with their backs facing us. We would notice these various mediations, devices and their cables before even having a chance to glance around the room. This seemingly small installation decision is particularly appropriate for an exhibition aiming to show the diverse and antagonistic views of this particular episode: the development of a hydroelectric project on the James Bay river, the prospects of job creation and energy production defended by technocrats and politicians, the exploitation of nature, and the threat to the culture and way of life of the Cree communities in James Bay.

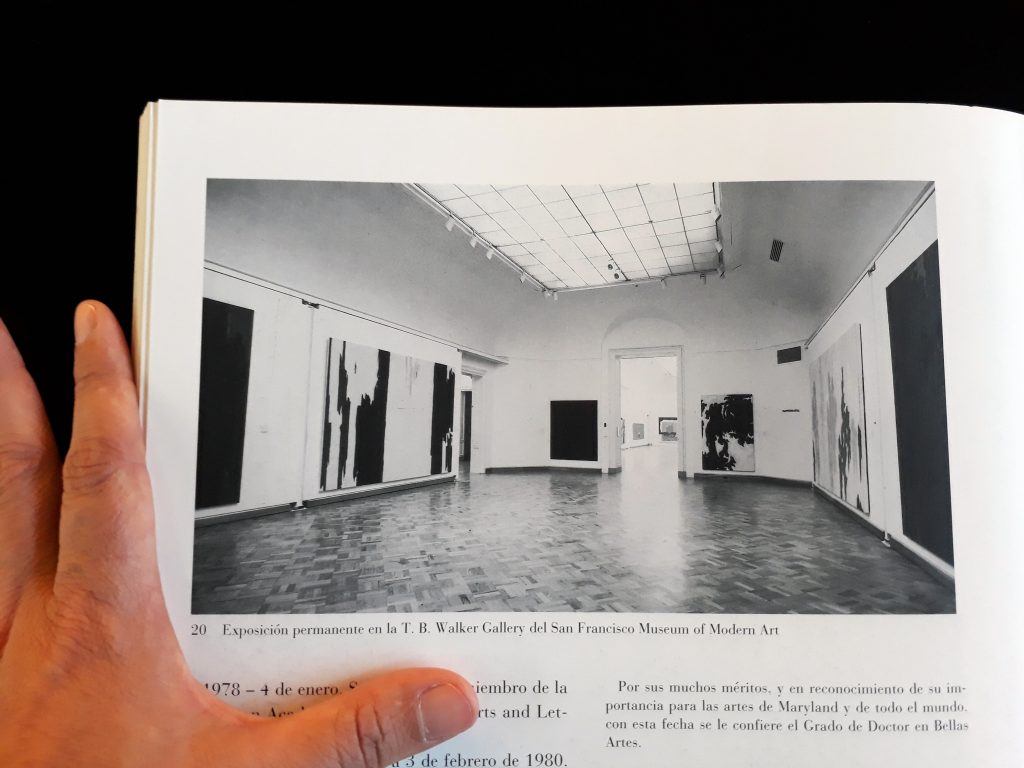

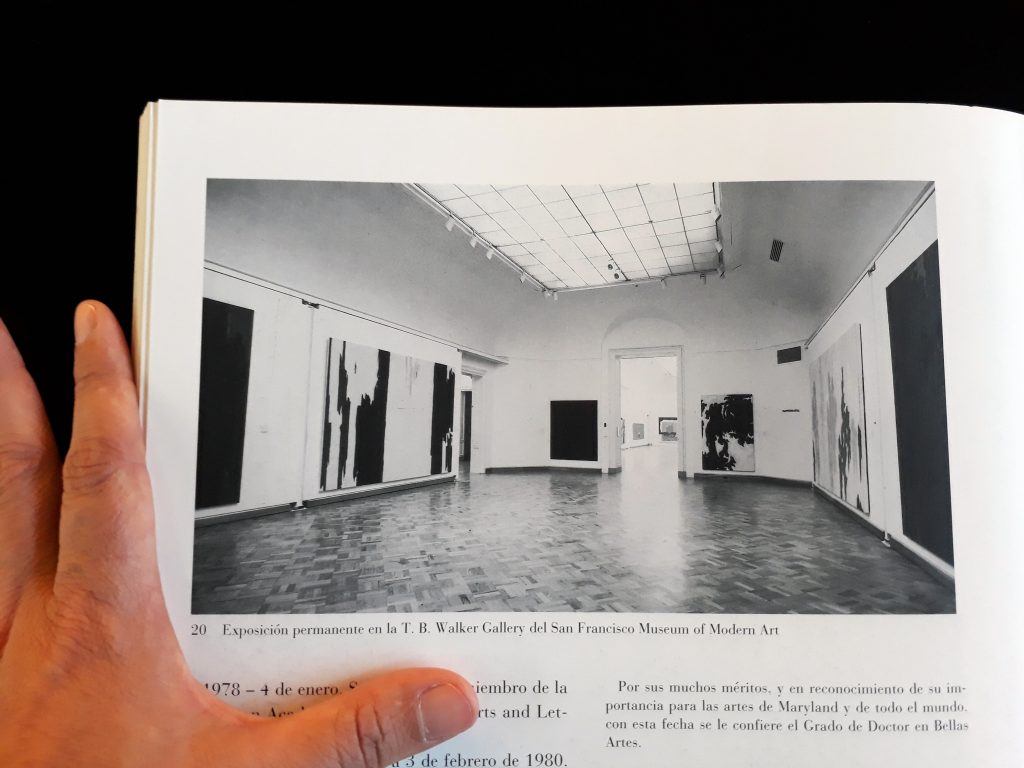

View of the exhibition “James Bay Project, A River Drowned by Water,” curated by Rolando Castellón, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1981. Courtesy: Rolando Castellón.

To install the exhibition, Castellón temporarily obscured a set of paintings by Clyfford Still in the T. B. Walker Gallery, which contained 28 canvases donated to SFMOMA by the artist in 1975. The donation agreement stipulated that the artworks be exhibited permanently in a gallery equipped with mobile partitions, so that the paintings not on view could be stored in the same space. The contract also stated, “it is the expectation of the Museum that for many years to come some of the paintings will always be on display.”

Between the donation and the temporary deinstallation of the works, only six years had passed, and only one since Still’s death. Although the use of the room remained within the scope of the agreement between the artist and the institution, Castellón’s bold decision was immediately questioned. In the pages of the San Francisco Chronicle, the art critic Thomas Albright lamented that the “inaccessibility of the Still paintings, even temporarily, raises a possible legal question” due to the donation contract. It is well known that one of Still’s most stubborn demands, in life and last testament, was that his works not be exhibited alongside those of other artists. With this temporary occupation of the gallery, Castellón was able to relate Still’s works to other elements, including the pieces of Cree material culture that were in Wittenborn and Biegert’s exhibition. Though they weren’t visible to visitors, Still’s paintings did remain on those walls, behind the partitions, stored alongside the rest of the museum’s Still holdings, as well as in the memory of some spectators, as the critic’s comment proved.

Perhaps it was merely a question of logistics, but this gesture of occupying the room of the great abstract painter with Indigenous themes and objects questioned the museum as an institution. In an essay dedicated to Castellón, Brazilian writer and curator Paulo Herkenhoff sees in this gesture “a historical metaphor for Rolando Castellón’s positions.” He states:

The incident and the destruction of the reservation would constitute what Castellón defines as the history of humanity against itself, which is an issue present in all his work. “Racism,” says Castellón, “is nothing but the fear that someone will take someone else’s place. The interesting part of my poor philosophy is the idea that after the invasion the culture was abused; that the conquerors will stay permanently in a higher position and will destroy everything.”

“Art hidden from view,” lamented the critic, and we could ask ourselves what other concealment processes take place in the museum. Rolando once shared an anecdote with me: he was in his office at SFMOMA when the director, Henry Hopkins, walked by and Rolando called after him. He wanted to show him something; it was a woven cloth made by his mother, Berta Alegría, inspired by an Indigenous textile that she had come across as a souvenir. Castellón turned the garment horizontally and posed a question to Hopkins. The director, under whose management SFMOMA had obtained Still’s major donation, responded: it looks like Clyfford Still. By changing the angle to reveal a Still, Castellón joked about possible “influences” for an artist who always stood against these, as the great defender of a self-generated and self-sufficient art.

Berta Alegría, textile. Courtesy: Rolando Castellón.

While Castellón temporarily disobeyed stipulations for the permanent installation of Still’s works in the museum, this episode allows us to get closer to his way of understanding curatorial practice and the exhibition itself. He confronted the “always” of timeless values with the “now,” with the necessity or the opportunity of curating an exhibition rooted within a specific context. As such, we can assume that political and environmental urgencies justified the temporary occupation of SFMOMA’s permanent rooms with an exhibition accused of being “pure propaganda.” Perhaps because, in contrast to Still—who, according to his authorized biography, “warned very early on about the need to separate his art from the elementary problems of subsistence”—the themes addressed by Wittenborn’s exhibition deal with subsistence, that of the James Bay Cree, and, widely speaking, life on this planet.

Clifford Still [sic] never picked mangoes, although artist Flavio Garciandía claims otherwise. Clifford Still never saw San Francisco, as he himself asserted: “The city, its artists and its history did not interest me at all. I had things to do.” During the decades he lived in San Francisco, Rolando Castellón also had things to do, including taking an interest in the city and its artists, including those from Latino, Chicano, Asian, and African American communities. Because of his ties to these communities and his experience with Galería de la Raza, which he co-founded in the city in 1969, the SFMOMA called him in 1972 to head a new program: the Museum Intercommunity Exchange (MIX). While he had no academic qualifications or prior museum experience, Castellón nonetheless possessed an exceptional knowledge of the art produced by the vast “minorities” of the San Francisco Bay Area. This accumulated knowledge came largely from his years of training through viewing art. Rolando told me that when he arrived in the city in the late 1950s, he was impressed by its intense artistic activity, and that in the years that followed, he did not want to miss a single exhibition opening at galleries, museums, or independent spaces.

Castellón was—and surely remains—a foreigner, an immigrant with an interest in what his neighbors are doing. Today, he maintains his practice as a curator and cultural agitator, guided by a commitment to local work, be it the San Francisco Bay Area of the 1970s and 80s, the Central America of the 90s, or the Costa Rica of the past two decades. Throughout his practice, the exhibition implies a politics of vicinity, privileging that which is nearest, as well as a poetics of vicinity, which may be understood as the act of bringing together.

Castellón speaks of his politics in terms of a “one-to-one scale,” which I recognize in his work. He speaks of time, attention to each element and each collaborator, which in his case can signify artists, friends, and audiences, as well as the plants, seeds, and insects in his artworks. The large-scale format of gallery walls is not at odds with dedication to small details. And his exhibitions are living creatures that transform over time. Tending to the artworks daily, he occasionally pretends to be a museum guard. Other times—as in the two retrospectives of his practice that he and I curated together in 2005 and 2016—he moves his whole studio to the gallery, transforming it into a space of work, pedagogy, and hospitality.

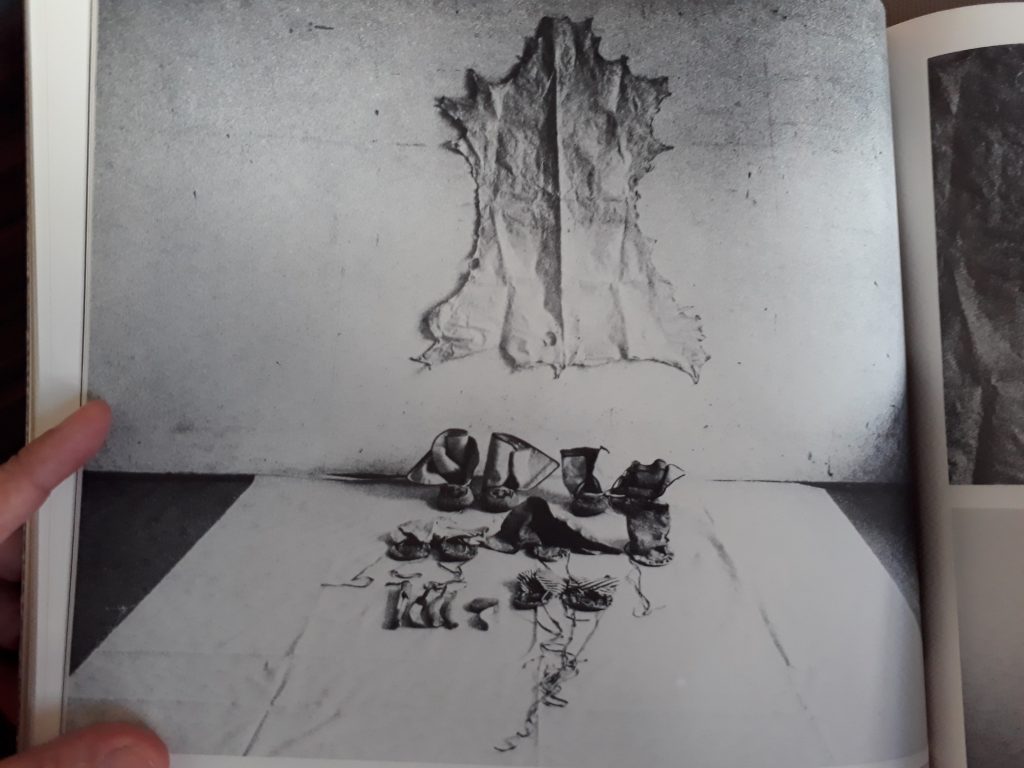

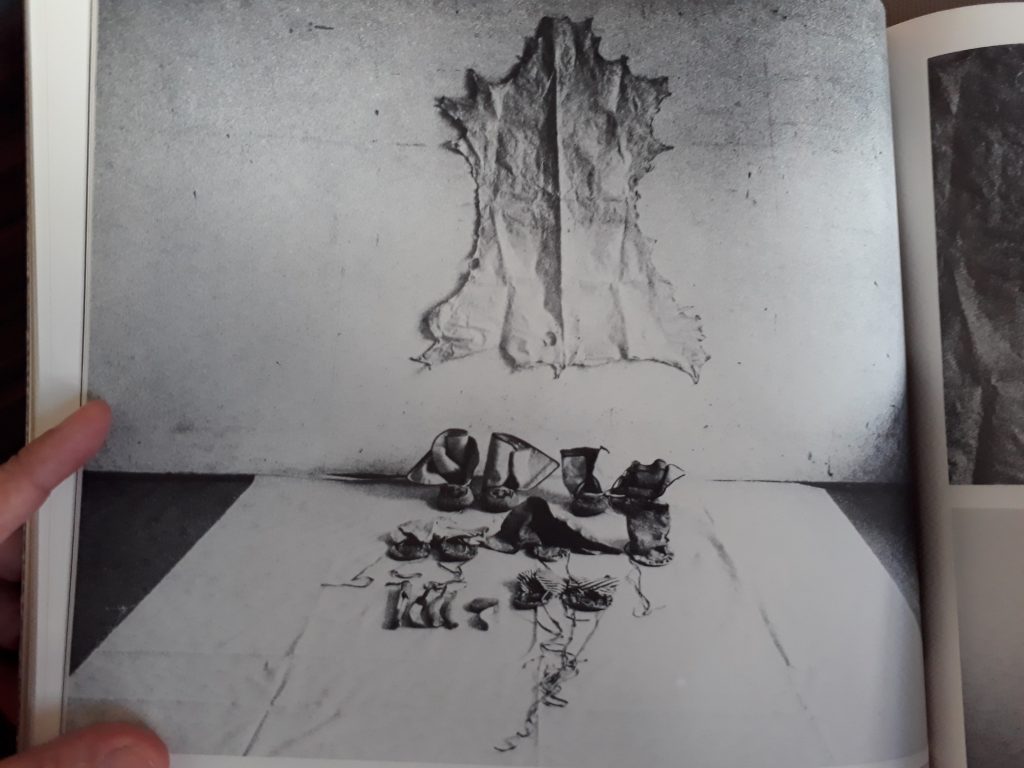

“One-to-one,” for Castellón, also implies a certain symmetry in the relationships between these elements. Wittenborn and Biegert’s “James Bay Project” foregrounded issues of scale and perspective, establishing a contrast between the view of the territory from above, that of airplanes and satellites, with the view from the ground and water. To materialize this comparison, they juxtaposed maps, statistics, diagrams, and legal documents with hunting utensils, furs, feathers, and footwear. By highlighting the Cree perspective, the “James Bay Project” showed what Indigenous knowledge already recognizes: a dependence on nature and an attention to its cycles of recovery—which is entirely alien to its complete exploitation.

In 1981, after presenting “James Bay Project,” Castellón leaves SFMOMA. That same year, he begins to use mud as the fundamental material in all his artworks, either applying it as a pigment or as a constructive element. For an artist who constantly shifts the dates of his works and even the date of his birth, Castellón notes with uncharacteristic precision the date on which he begins to work with mud. The year 1981 is the same one he both leaves SFMOMA and gets divorced. I might not have related these events were it not for Rolando himself mentioning them in one of our conversations. I asked him about the mud, and he replied: “It was an act of courage to take a finished painting and put mud on it.” Elsewhere he affirmed: “When the mud came in, it sort of ‘amalgamized’ everything. It was like, I can draw, I can paint, I can sculpt over this thing, and the mud seems to keep things cohesive.”

Mud as resilience. For Castellón, the mixture of soil and water is not merely a malleable resource but an ethics, a vital position: “I use mud as a metaphor to describe the generosity of the earth. Mud is the material that best exemplifies the resistance of the oppressed races in their struggle for survival,” he explains. On the same dates—May to July 1981—on which Rolando Castellón the curator presented in San Francisco the exhibition about a dam that flooded Indigenous lands, Rolando Castellón the artist participated in Colombia in the IV Medellín Biennial with a set of mud-painted works. To accompany the paintings, he wrote what he called the “Post-Columbian Manifesto” with some of the humor and colonial critique that often manifests in his artistic and curatorial interventions.

When Castellón joined SFMOMA in 1972 to coordinate MIX, pedagogy was a key dimension of the program, in relation both to the public and to the institution itself. In an interview marking the 75th anniversary of the museum, Castellón stated that the rationale for MIX was entirely educational. The so-called Third World Curator—a title derived from the series of exhibitions he organized at SFMOMA—quickly understood that to achieve more effective change in the museum, MIX shouldn’t be a program segregated from curatorial initiatives, but instead needed to merge with the museum’s institutional goals. While the MIX acronym suggests a museum that is willing to mix, to transmit through only one of its pillars, it is apparent that the curator forced the institution to try a new, non-prophylactic policy of contact with regard to its immediate neighbors. Castellón succeeded, albeit temporarily, in convincing SFMOMA to respond to his demand, and in turn he became curator at the museum. To what extent the institution actually provided a real space for what it called “communities” in its policies of acquisition and collection or the distribution of its resources requires further scrutiny.

Deena Chalabi, currently the associate curator of public dialogue at SFMOMA, seems to have a less optimistic opinion. Chalabi recently said that upon her arrival at the museum in 2014, she visited the archives to better understand the Museum Intercommunity Exchange, as it could be a precursor to the type of work her department does today. After researching Castellón’s work at SFMOMA and his ties to Galería de la Raza, the curator concludes: “Despite these early connections, I find little else that explores the museum’s relationship over time to artistic communities of color in the Bay Area. […] Through the archive I’ve seen glimpses of different ways in which similar questions have animated the institution at different moments in its history. There are rarely fully satisfying answers.”

I like to think that, on the rare occasions that the museum did provide a more or less adequate answer, Castellón had something to do with it. Not because he was an expert with the right solutions to everything, but perhaps for just the opposite reason. Rolando is an amateur, a lover, in terms of his learning methods, but also in terms of his strong connection to artistic practice. He is amateur for the amount of time he dedicates to his work—without any claim to efficiency—and for his irreverent relationship to expert knowledge and the order of classifications. Castellón’s work rejects any hierarchy between systems of knowledge, such as the distinction between the so-called fine arts and the minor arts. In any of his exhibitions, as an artist or a curator, we might find—in equivalent display—a drawing by a known artist and a textile work by an unknown one, such as a simple kitchen cloth made by his mother.

Skins and shoes collected in the James Bay Territory by Rainer Wittenborn and Claus Biegert. Reproduced from the publication James Bay Project (Montreal: Montreal Museum of Fine Art, 1981), 222.

As if that famous question posed by Linda Nochlin in 1971—“Why have there been no great women artists?”—was simultaneously negated by an immigrant, racialized subject, the work of Castellón in San Francisco questioned both the artistic institution and what counts as art. His first gesture was to found the Galería de la Raza with a group of Chicano artists, as a response to conditions of discrimination and the need for a space of their own. Since its foundation in 1969–70, the gallery has represented both a community project and a political stance, staying involved in the struggles of the time and the civil rights movement. I like to think that some of that experience would later be sown into SFMOMA through Rolando Castellón.

The “James Bay Project” exhibition addressed the tension between knowledge and experience and questioned the notion of “expert” knowledge through the inclusion of a herbarium. Wittenborn and Biegert’s project included a large number of plants they collected during their trips through the James Bay Territory in Canada, which they both classified according to scientific botanical taxonomy and categorized according to methods suggested by the Cree community, including a shaman. In the interviews collected in the James Bay Project publication, two passages made me think about the knowledge that comes from experience. The first is an anecdote involving a fisherman and a biologist sent by the the state-run Department of Indian Affairs to guide fishermen to where they should fish and to point out all the things they should consider. The Cree fishermen followed him, doing everything the expert proposed, but the next day, the fishing nets remained empty. Finally, a local fisherman suggested where to go and the fishing nets came back full. The chief who tells the story remarked, “Indian Affairs had to recognize that we already are experts.”

The second anecdote appears in a conversation with Luci Salt, the only woman included in the interviews. She narrates her educational experience in a residential school in Ontario, where she lived with a white family during the school year and spent the summers with her Cree family. She explained: “In school you don’t have to do anything physical. We didn’t learn the feeling you need for the life back home. At that time I never learned to pluck a goose, because when I came home, the Spring goose season was over and all the kids left before the Fall goose hunt.” Returning to Castellón’s practice, I wonder if the knowledge transmitted by his exhibitions might be closer to the knowledge of the plucking of a goose, of a way of thinking gleaned from hands-on experience: work with what you have at hand, such as soil and water or the nearest surroundings and networks. Bypass the inflation of the single artwork through multiplicity and the costly economy of the original with processes of reproduction and recycling, of domestic production and self-publishing. A poor aesthetics and an economy of the possible.

A year ago, in the context of the X Bienal Centroamericana in San José, Costa Rica, which I curated, we dedicated a special project to Castellón—which to me was almost like a statement of intent for the entire event. We named the exhibition “Hábitat, the Living Work of Rolando Castellón Alegría,” thinking of his practice as a “place of appropriated conditions for the life of an organism, species, or animal or plant community.” He would say that in this space of hospitality we welcomed both organic elements and the works of other artists, friends, neighbors, and amateurs. With “Hábitat,” we tried to center on a politics that was focused not merely on themes or representation, but also on the poetics of Castellón’s methods and materials: poor materiality and the reuse of waste or vulnerable conditions were part of this “live work,” of this “life-work.”

From my perspective, Castellón’s exhibition implicated a political gesture, which I like to read alongside the presence of activist Berta Cáceres in a few of the artworks shown in the X Bienal Centroamericana. In March 2016, after years of threats for her opposition to the privatization of rivers and lands by hydroelectric, mining, and logging companies, the Lenca activist was assassinated. It is well known that Honduras—at least up until this year—is the country with the highest rate of assassinations of environmental activists in the world and that the majority of these killings remain unresolved. Cáceres appears in the drawing Historia de la politica de las Flores 4, exhibited by the artist the artist duo Jeleton at one of the biennial’s venues. In another venue, images of the mass funeral of the “guardian of the rivers” were included in a photographic essay by Delmer Membreño which records conflicts for land and the increasing vulnerability of farmers, worsened by new laws and state practices that protect large landowners and multinational corporations.

View of the exhibition “Hábitat. Obra viva de Rolando Castellón Alegría,” curated by Tamara Díaz Bringas, X Bienal Centroamericana, San José, Costa Rica, 2016. Photo: Flavia Sánchez.

In 1981, the “James Bay Project” exhibition in San Francisco denounced the flooding of Indigenous lands by a mega-hydroelectric project. In San Francisco, in April 2015, Berta Cáceres received the Goldman Environmental Prize, in recognition of her activism with the Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH), which halted the construction of a hydroelectric project that would have privatized the Gualcarque River. In her acceptance speech, just a year before she was murdered, the activist declared: “Wake up! Wake up, humanity! There is no more time. Our consciousness will be moved by the fact that we sit contemplating our self-destruction by capitalist, racist, and patriarchal depredation. The Gualcarque River is calling on us, just as are all those who are seriously threatened. We have to heed their call. Our militarized, encircled, and poisoned Mother Earth, where fundamental rights are systematically violated, demands that we act.”

—

Translated by Paula Villanueva Ordás

This essay is a modified version of a talk presented by Tamara Díaz Bringas for The Paper of the Exhibition (1977-2017) at the International Curating Symposium, organized by Bulegoa and Azkuna Zentroa, Bilbao, Spain, 21-23 September 2017.

BIO

Tamara Díaz Bringas is a researcher and independent curator. She was Chief Curator of the X Bienal Centroamericana (San José, Costa Rica) in 2016. In 1996, she earned her BA in Art History from the University of Havana; in 2009, she graduated from the Independent Studies Program at MACBA (Barcelona, Spain); and from 2011 to 2013, she held a research fellowship at the Museo Reina Sofía (Madrid, Spain). Between 1999 and 2009, she was Curator and Editorial Coordinator at TEOR/éTica (San José, Costa Rica). Some of her curatorial projects include “Playgrounds. Reinventar la plaza,” with Manuel J. Borja-Villel and Teresa Velázquez, at Museo Reina Sofía (Madrid, Spain, 2014); “The Doubtful Strait,” with Virginia Pérez-Ratton, at TEOR/éTica (San José, Costa Rica, 2006); and “Rolando Castellón,” at Museo de Arte y Diseño Contemporáneo (San José, Costa Rica, 2005). In 2016, TEOR/éTica published a selection of her essays, Crítica próxima, as the first volume of their “Escrituras Locales: Posiciones Críticas desde Centroamérica, el Caribe y sus Diásporas” series.

El siguiente es un extracto del ensayo “Si el agua no ahogase un río” (2017) escrito por la curadora Tamara Díaz Bringas.

Comenzando por la exhibición “James Bay Project, A River Drowned by Water” (SFMOMA, 1981), en el texto Díaz Bringas realiza un estudio de caso y reflexiona acerca de la práctica y la metodología de Rolando Castellón, artista y curador Nicaragüense. Aunque Castellón es celebrado por sus importantes contribuciones en los contextos artísticos centroamericanos, su trabajo en los Estados Unidos entre el 1956 y 1992 es poco conocido en el discurso internacional del arte contemporáneo y la historia del arte. Por medio de esta contribución, Díaz Bringas ilumina un importante precedente del tipo de exposición política, activista e investigativa tan común en nuestros días. Reintroduciéndo así a Castellón al público de habla inglesa como una figura innovadora que opera entre los mundos del arte Nicaragüense, Costarricense y Estadounidense.

—

“James Bay Project, Un río ahogado por el agua” fue una exposición itinerante del artista alemán Rainer Wittenborn y el escritor Claus Biegert en torno a una represa que inundó tierras indígenas en el norte de Canadá. Con el apoyo del Instituto Goethe, el proyecto se exhibió en el Museo de Arte Moderno de San Francisco entre mayo y julio de 1981, constituyendo además la última exposición presentada por Rolando Castellón Alegría (Nicaragua, 1937) en sus años de trabajo en esa institución. Propongo aquí atender a la práctica del artista y curador nicaragüense a través de algunos documentos y gestos de aquella muestra.

Si entrásemos –del modo en que nos es posible hoy, a través del archivo– en las salas del SFMOMA en la primavera de 1981, encontraremos dos monitores que nos dan la espalda. Tendríamos que reparar en el dispositivo antes de siquiera asomarnos a la sala. Los medios, las mediaciones, están a la vista. Esa pequeña decisión de montaje parece especialmente acertada en una exposición que intentaba presentar los diversos, antagónicos enfoques sobre un episodio: el proyecto de desarrollo hidroeléctrico de la Bahía James, las expectativas de creación de empleo y producción de electricidad sostenidas por políticos y técnicos, la explotación de la naturaleza y la amenaza a las formas de vida y a la cultura de los indígenas Cree.

Para el montaje de esa muestra, Castellón se atrevió nada menos que a descolgar las pinturas de Clyfford Still de su espacio habitual en el museo. La T.B. Walker Gallery estaba destinada a alojar de manera permanente la colección de 28 pinturas que Still había donado al SFMOMA en 1975. En el acuerdo de donación quedaba escrito que tanto la exposición como el almacenamiento de esas obras se haría en una galería acondicionada con tabiques móviles, que permitiesen guardar en el mismo espacio las pinturas no expuestas. El contrato menciona además la “expectativa del Museo de que durante muchos años por venir algunas de las pinturas estarán siempre en exhibición”.

Entre la donación y el desmontaje temporal de las obras habían pasado apenas seis años, y sólo uno desde la muerte de Still. Aunque el uso de la sala se mantuvo dentro de los márgenes que permitía el acuerdo firmado entre el artista y la institución, semejante atrevimiento resultó cuestionado de inmediato. Desde las páginas del San Francisco Chronicle, Thomas Albright lamentaba la inaccesibilidad a las pinturas de Still, agitando el fantasma de “posibles cuestiones legales” a causa del contrato de donación. Se sabe que una de las demandas más obstinadas de Still, en vida y testamento, es que sus obras no se exhiban con las de otros artistas. Con el gesto de ocupación temporal de la sala, Castellón lograba poner las obras de Still en relación a otras producciones, incluyendo elementos de cultura material de los indígenas Cree que estaban en la exposición de Wittenborn. Las pinturas de Still permanecían en aquellos muros: tras los tabiques que permitían almacenarlas en la propia galería, pero también –como probaba la nota del crítico– en la memoria de algunos espectadores.

Clyfford Still Room at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Reproduced from the catalogue Clyfford Still (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 1992).

Tal vez era sólo una cuestión logística, pero el gesto de ocupar la sala del gran pintor abstracto con temas y producciones indígenas colaba de paso una interpelación al museo. En un ensayo dedicado al artista nicaragüense, Paulo Herkenhoff veía en ese gesto “una metáfora histórica de las posiciones de Rolando Castellón”: “El episodio y la destrucción de la reserva –escribe el curador brasileño– compondrían aquello que Castellón define como la historia de la humanidad contra sí misma. Es la cuestión que estará presente en su obra. ‘El racismo –dice Castellón citado por Herkenhoff– no es más que el miedo de que alguien vaya a tomar la posición de otra persona. Lo que interesa de mi filosofía pobre es la idea de que, después de la invasión hubo abuso de cultura; que los que conquistaron se quedaron permanentemente en la condición de superior y que destruyeron todo, hasta todo desaparecer’”.

“Arte oculto a la vista”, lamentaba el crítico, y podríamos preguntarnos qué otros procesos de ocultación tienen lugar en el museo. Una anécdota que me ha contado Rolando lo ubica en su oficina en el SFMOMA mientras pasa por allí su director y Castellón lo llama para mostrarle algo. Se trata de un tejido hecho por su madre e inspirado en un textil indígena que ella, Berta Alegría, había conocido a través de un souvenir. Castellón gira la prenda en posición horizontal y le dirige una pregunta a Henry Hopkins. El director, bajo cuya gestión se había conseguido la importante donación de Still al SFMOMA, responde: Clyfford Still. Con el gesto de girar el plano para encontrar un Still, Castellón bromeaba sobre las posibles “influencias” en el artista más refractario a éstas, el gran valedor de un arte autogenerado y autosuficiente.

Si la expectativa de permanencia “para siempre” de las obras de Still en el Museo había sido temporalmente desobedecida por Castellón, ese episodio nos permite acercarnos a su modo de entender la práctica curatorial y la exposición. Confrontar el “siempre” de los valores atemporales con un “ahora”, con la necesidad o la oportunidad de una exposición en un contexto específico. Podemos imaginar que eran urgencias políticas las que justificaron la ocupación temporal de las salas permanentes del Museo de Arte Moderno con una exposición acusada de “pura propaganda”. Quizás porque en contraste con Clyfford Still –quien según su biografía autorizada “advirtió muy pronto la necesidad de separar su arte de los problemas elementales de subsistencia”–, las cuestiones encaradas por la exposición de Wittenborn tenían que ver con subsistencia, la de los indígenas Cree en James Bay, e incluso la de la vida en el planeta.

Clifford Still [sic] nunca recogió mangos, aunque Flavio Garciandía afirme lo contrario. Clifford Still nunca miró a San Francisco, según él mismo afirmó: “La ciudad, sus artistas y su historia no me interesaban nada. Tenía cosas que hacer”. Por su parte, Rolando Castellón tenía cosas que hacer, incluyendo el interesarse por la ciudad y sus artistas, incluyendo los de comunidades latinas, chicanas, asiáticas, afroamericanas. Por sus vínculos con esas comunidades y su experiencia con Galería de la Raza, de la que fue cofundador en 1969 y su primer director, el San Francisco Museum lo llamó en el 72 para encabezar un nuevo programa: el Museum Intercommunity Exchange (MIX). Sin títulos académicos ni trayectoria institucional previa, Castellón contaba sin embargo con un conocimiento excepcional del arte producido por vastas “minorías” en el área de la bahía de San Francisco. Y ese saber acumulado se debía en buena medida a su entrenamiento como espectador. Cuenta Rolando que al llegar a la ciudad a fines de los cincuenta quedó impresionado por su intensa actividad artística, y en los años siguientes, no quiso perderse cuanta exposición abriese en galerías, museos o espacios independientes.

Castellón era entonces –y seguramente no ha dejado de serlo– un extranjero, un inmigrante al que le interesa lo que hacen sus vecinos. Su desempeño como curador y agitador cultural ha estado guiado por un compromiso con el trabajo local, sea el del área de la bahía de San Francisco de los setenta y ochenta, la Centroamérica de los noventa o los artistas costarricenses de las últimas dos décadas. En su práctica, la exposición supone una política de la vecindad, un atender a lo más próximo. Y una poética de la vecindad, una gracia en el poner juntos.

Cuando Castellón habla de su política en términos de “one-to-one”, creo reconocer en su propia obra lo que dice. Habla de tiempo, de la atención puesta en cada elemento y cada colaborador, que en su caso puede tratarse tanto de artistas, amigos y públicos como de plantas, semillas o insectos. El gran formato, el de los muros, no está reñido con la dedicación a los pequeños detalles. Y sus exposiciones son criaturas vivas que se van transformando en el tiempo. Para acompañar las muestras con cuidados cotidianos, en alguna ocasión se ha hecho pasar por vigilante de sala. Otras veces –como en las dos revisiones de su obra que curamos juntos en 2005 y 2016– mueve su estudio a la sala, transformándola en espacio de trabajo, pedagogía y hospitalidad.

View of the exhibition “Rastros. Una mirada cíclica a la obra de Rolando Castellón,” curated by Tamara Díaz Bringas, Museo de Arte y Diseño Contemporáneo, San José, Costa Rica, 2005. Photo: Roberto Vargas.

“Uno a uno” implica también cierta simetría en la relación. En James Bay Project las cuestiones de escala y punto de vista aparecían en primer plano. El proyecto de Wittenborn y Biegert establecía un contraste entre la mirada al territorio desde arriba, la de aviones y satélites, y la que de quien se relaciona con éste desde el andar, en canoas o raquetas de nieve. La yuxtaposición de mapas, estadísticas, diagramas, documentos legales, junto a utensilios de caza, pieles, plumas o calzado ponía en materia el contrapunto. La publicación lo ponía en texto. Pero lo que muestra James Bay Project desde la perspectiva de los indígenas es el saberse dependientes de la naturaleza, lo que significa ajenos a una idea de explotación total de ésta y atentos a sus ciclos de recuperación.

En 1981, luego de presentar Un río ahogado por el agua, Castellón sale del San Francisco Museum. Ese mismo año comienza a utilizar barro como materia fundamental de sus obras. Barro aplicado como pigmento o en tanto elemento constructivo. El artista que juega constantemente con las fechas, moviendo a su antojo la datación de sus obras o su propio nacimiento, anota con desacostumbrada precisión el inicio de su trabajo con el barro. Lo ubica en 1981, el año en que sale del SFMOMA y se divorcia. Tal vez yo no habría puesto en relación esas experiencias de no ser porque el mismo Rolando las mencionó en una de nuestras conversaciones, a raíz de que le preguntase por el barro, y dijese: “fue un acto de valor coger una pintura ya hecha y ponerle barro”. Y en otro lugar afirmaba: “Cuando entró el barro, lo amalgamó todo. Era como que puedo dibujar, pintar, esculpir y el barro parece mantener las cosas cohesionadas”.

El lodo como resiliencia. En Castellón la mezcla de tierra y agua no supone un mero recurso plástico sino una ética y una posición vital: “Uso barro como una metáfora para describir la generosidad de la tierra. Barro es la materia que mejor ejemplifica la resistencia de las razas oprimidas en su lucha por la supervivencia”, escribe. En las mismas fechas (mayo a julio de 1981) en que el curador Rolando Castellón presentaba en San Francisco aquella exposición en torno a una represa que inundó tierras indígenas, el artista Rolando Castellón participa con un conjunto de obras pintadas con barro en la IV Bienal de Medellín, Colombia. Para acompañarlas escribe, con algo del humor y crítica colonial que suele colar en sus intervenciones, un así llamado “Manifiesto pos-colombino”.

Cuando Castellón entró al SFMOMA en 1972 para coordinar el MIX, la dimensión pedagógica resultó clave en el programa, en relación a los públicos en igual medida que a la propia institución. En una entrevista que le hicieran en el 75 aniversario del Museo, Castellón asegura que toda la razón del MIX fue educativa. El llamado “Curador del Tercer Mundo” –seguramente por la serie de exposiciones que organizó en el SFMOMA bajo ese título– entendió pronto que para conseguir transformaciones más efectivas en el museo, el MIX debía dejar de ser un programa segregado y devenir un enfoque transversal en los objetivos de la institución. Si el acrónimo “MIX” nos sugiere un museo dispuesto a la mezcla, al contagio sólo a través de una de sus patas, podemos pensar que el curador forzó a la institución a ensayar una nueva política –no profiláctica– con sus vecinos. Castellón consiguió, al menos provisionalmente, que el SFMOMA respondiese a esa demanda y fue así que se convirtió en curador regular del museo hasta 1981. Habría que ver, sin embargo, en qué medida la institución dio espacio real a lo que llamaba “comunidades” en sus políticas de adquisición, colección o en la distribución de sus recursos.

La respuesta de una curadora actual en el SFMOMA no es muy optimista. Deena Chalabi contaba hace poco que a su llegada al museo en 2014 recurrió a los archivos para entender más sobre el Museum Intercommunity Exchange, considerando que podría ser un precursor del tipo de trabajo que hace hoy su departamento, llamado “Public Dialogue”. Luego de referirse al trabajo de Castellón en el SFMOMA y su vinculación con Galería de la Raza, la curadora concluye: “A pesar de esas tempranas conexiones, encuentro poco más que explore a través del tiempo la relación del museo con comunidades artísticas de color en Bay Area. […] A través del archivo he podido vislumbrar los distintos modos en que preguntas parecidas han animado a la institución en diferentes momentos de su historia. Rara vez hay respuestas plenamente satisfactorias”.

Me gustaría pensar que en alguna rara vez en que el museo dio una respuesta más o menos adecuada, pudo estar Castellón por ahí. No porque fuese el experto con soluciones apropiadas para cada cosa, sino quizás por todo lo contrario. Rolando es el amateur, el amador, en cuanto a sus formas de aprendizaje, pero también por su vinculación a una práctica. Amateur por la cantidad de tiempo –sin idea de eficiencia– que dedica a su trabajo, y por su relación irreverente con el saber experto, con el orden de las clasificaciones. El hacer de Castellón rechaza las jerarquías entre los saberes, como entre las llamadas “bellas artes” y “artes menores” por ejemplo. Y en cualquier exposición suya, en tanto artista o curador, podríamos encontrar en situación equivalente el dibujo de un autor conocido o una pieza textil, como un sencillo paño de cocina compuesto por su madre.

Como si aquella pregunta de Linda Nochlin en 1971 –¿por qué no ha habido grandes mujeres artistas?– fuese simultáneamente declinada por un inmigrante, un sujeto racializado, en San Francisco, el trabajo de Castellón implicó a menudo un cuestionamiento de la institución artística y de lo que se entiende por arte. El primer gesto fue fundar junto a un grupo de artistas chicanos la Galería de la Raza, como una respuesta a condiciones de discriminación y a la necesidad de un espacio propio. Desde su fundación en 1969-1970, la Galería implicó un proyecto comunitario y un posicionamiento político, cercano a las luchas de ese momento y al movimiento por los derechos civiles. Me gusta pensar que algo de aquella experiencia se colaría luego en el SFMOMA a través de Rolando Castellón.

En Un río ahogado por el agua, la tensión entre saberes y experiencias, y una revisión del saber “experto”, se abordaba en la figura del herbario. El proyecto de Wittenborn y Biegert incluyó una gran cantidad de plantas recolectadas por ambos en sus viajes por el norte de Canadá, y clasificadas según dos lógicas: una, la de científicos y botánicos; otra, la sugerida por un grupo de indígenas, incluyendo un chamán. En las entrevistas recogidas en la misma publicación de James Bay Project, dos pasajes me hicieron pensar en el saber del hacer. El primero es una anécdota que involucra a un pescador y un biólogo, cuando éste es enviado por el programa estatal de “Indian Affairs” para guiar a los pescadores sobre dónde deben pescar y todo lo que deben tener en cuenta. Los pescadores Cree lo siguen, haciendo todo lo que el experto les propone, pero al día siguiente, la red está vacía. Entonces es un pescador quien sugiere adónde ir y las redes se llenan, lo que le hace decir al jefe indígena que narra la anécdota: “Indian Affairs tuvo que reconocer que nosotros ya somos expertos”.

El segundo pasaje aparece en la conversación con Luci Salt, la única mujer que toma voz en las entrevistas, cuando narra su experiencia educativa en una escuela en Ontario, donde vivía con una familia blanca durante el curso escolar y pasaba los veranos con su familia Cree: “En la escuela nunca tienes que hacer nada físico. Nunca aprendimos la sensibilidad que necesitas para la vida de vuelta a casa. En ese tiempo nunca aprendí a desplumar un ganso, porque cuando volvía a casa ya la temporada primaveral de gansos había pasado y los niños nos íbamos antes de que empezara la caza de gansos de otoño”. De vuelta a la práctica de Rolando Castellón, me pregunto si su saber respecto a la exposición sería más cercano a ese cómo desplumar un ganso o a un pensar desde el hacer. Trabajar con lo que tiene a mano, la tierra y el agua por ejemplo, o bien, el entorno más cercano y sus redes. Sortear la inflación de la obra única con lo múltiple, y la costosa economía del original con procesos de reproducción y reciclaje, de producción casera y autoedición. La estética pobre y la economía posible.

Installation detail, “Hábitat. Obra viva de Rolando Castellón Alegría,” curated by Tamara Díaz Bringas, X Bienal Centroamericana, San José, Costa Rica, 2016, Photo: Flavia Sánchez.

Hace un año, en el contexto de la X Bienal Centroamericana, de que fui curadora general, dedicamos a Castellón un proyecto especial –que para mí significaba casi una declaración de intenciones de todo el evento. Llamamos a la muestra Hábitat. Obra viva de Rolando Castellón Alegría, pensando en su trabajo como ese “lugar de condiciones apropiadas para que viva un organismo, especie o comunidad animal o vegetal”. Decía entonces que en ese espacio de hospitalidad pueden encontrar acogida tanto elementos orgánicos como las obras de otros artistas, amigos, vecinos y aficionados. Con Hábitat en la Bienal intentaba dar centralidad a una política que no se alojase sólo en el plano de la representación o de los temas, sino en la propia poética de los materiales y métodos de Castellón: la materialidad pobre, la reutilización del desecho o la condición vulnerable son parte de esa “obra viva”, de esa “obra vida”.

Desde mi perspectiva, la exposición de Castellón implicaba también un gesto político, que me gusta leer en paralelo a la presencia de Berta Cáceres en unas pocas obras –aunque muchas horas– de la X Bienal Centroamericana. En marzo de 2016, luego de años de amenazas por su oposición a la privatización de ríos y territorios por empresas hidroeléctricas, mineras y madereras en Honduras, la activista lenca fue asesinada. Se sabe que Honduras –al menos hasta inicios de este año– es el país con mayor índice de asesinatos de activistas ambientales y que la mayor parte de éstos quedan impunes. Berta Cáceres aparecía dibujada en la Historia de política de las flores 4, que presentó Jeleton en una de las sedes de la bienal. En otra, se mostraban imágenes del multitudinario funeral de la llamada “guardiana de los ríos”, incluidas en un ensayo fotográfico de Delmer Membreño que registra los conflictos por la tierra y la creciente vulnerabilidad de los campesinos, agudizada con nuevas leyes y prácticas del Estado que protegen a grandes terratenientes y al capital transnacional.

En 1981 la exposición James Bay Project en San Francisco denunciaba la inundación de tierras indígenas por un mega-proyecto hidroeléctrico. En San Francisco, pero en abril de 2015, Berta Cáceres recibía el Premio Ambiental Goldman, en reconocimiento a su activismo junto al movimiento COPINH, que logró parar la construcción de un proyecto hidroeléctrico que privatizaría el río Gualcarque en Honduras. En su discurso de aceptación del premio, apenas un año antes de ser asesinada, la activista lenca declaraba: “¡Despertemos! ¡Despertemos Humanidad! Ya no hay tiempo. Nuestras conciencias serán sacudidas por el hecho de sólo estar contemplando la autodestrucción basada en la depredación capitalista, racista y patriarcal. El Río Gualcarque nos ha llamado, así como los demás que están seriamente amenazados. Debemos acudir. La Madre Tierra militarizada, cercada, envenenada, donde se violan sistemáticamente los derechos elementales, nos exige actuar”.

—

Este ensayo es la versión modificada de una charla presentada por Tamara Díaz Bringas en El ensayo de la exposición (1977-2017), Simposio Internacional de Comisariado, organizado por Bulegoa y Azkuna Zentroa, Bilbao, 21-23 septiembre 2017.

BIO

Tamara Díaz Bringas es investigadora y curadora independiente. Ha sido curadora general de la X Bienal Centroamericana, 2016. En 1996 se licenció en Historia del Arte por la Universidad de La Habana. Graduada en 2009 del Programa de Estudios Independientes del MACBA, Barcelona. De 2011 a 2013 tuvo una beca de investigación en el Museo Reina Sofía, de Madrid. Entre 1999 y 2009 se desempeñó como curadora adjunta y coordinadora editorial en TEOR/éTica, San José. Entre sus curadurías se cuentan: Playgrounds. Reinventar la plaza (junto a Manuel J. Borja-Villel y Teresa Velázquez), Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid, 2014; Estrecho Dudoso (junto a Virginia Pérez-Ratton), TEOR/éTica, San José, 2006; Rolando Castellón, Museo de Arte y Diseño Contemporáneo, San José, 2005. TEOR/éTica ha publicado una selección de sus ensayos en el libro Crítica próxima (2016), el primer volumen de la serie “Escrituras Locales: Posiciones Críticas desde Centroamérica, el Caribe y sus Diásporas.”