What follows is a transcript of an address delivered by an unnamed audio engineer to a conference of the Audio Engineering Society some time in the mid-2000s. In constructing the transcript, the author employed recordings from his archive of materials related to audiophile culture and the pursuit of realism in the reproduction of sound. This archive forms the basis of Improving on Perfection, a series of projects—essays, fictions, audio works, and performances—that addresses how we determine what sound should sound like; and how human subjects (and their cultural biases and biological characteristics) are apprehended by and incorporated into technological systems. The transcript is accompanied by two videos designed to test the reader’s speakers.

***

You’ve never heard anything like it. You hear the whole sound first. And when you catch your breath you search for words to describe the depth, the detail, the etched precision of the music. That stunning pair of three-way speakers is sending clean, undistorted sound to every corner of the room. At every frequency. At every level. Loud or soft. High or low. It doesn’t matter. The energy is constant. You’re experiencing three-dimensional imaging: vocal up front. Lead guitar two steps back and one to the left. Drums further back. The piano closer, almost at the edge of the sound. Suddenly you’re aware of a fullness in the music that you’ve heard before but never associated with recorded sound.

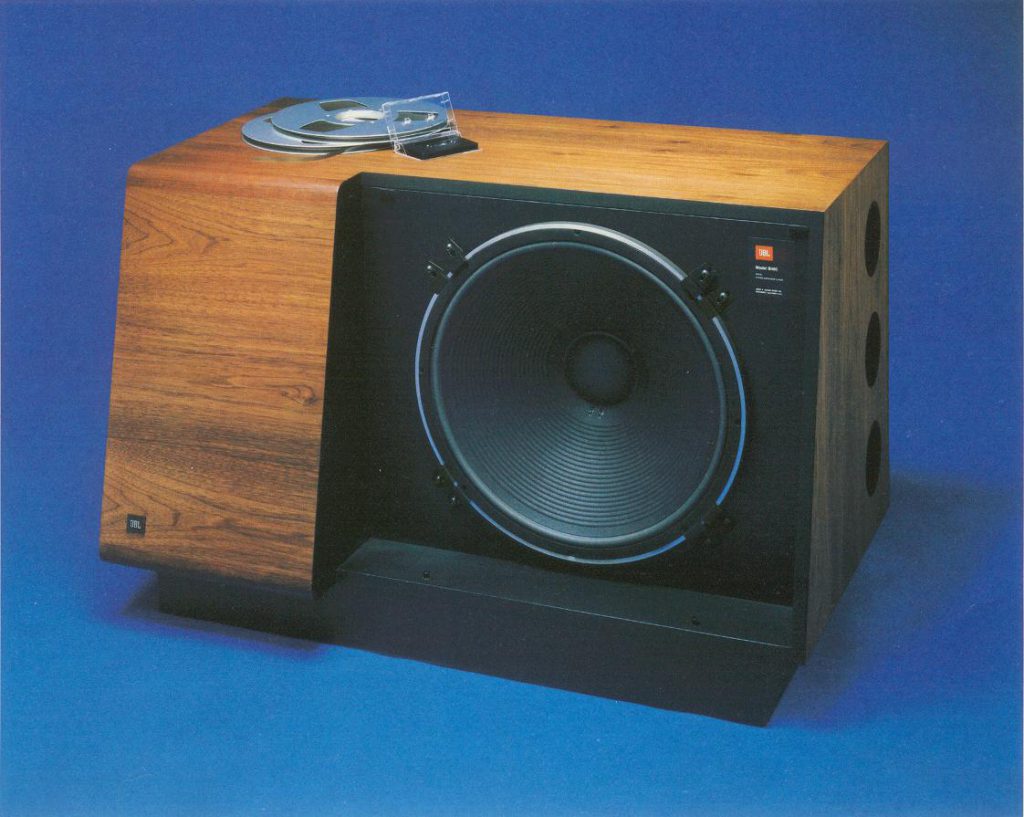

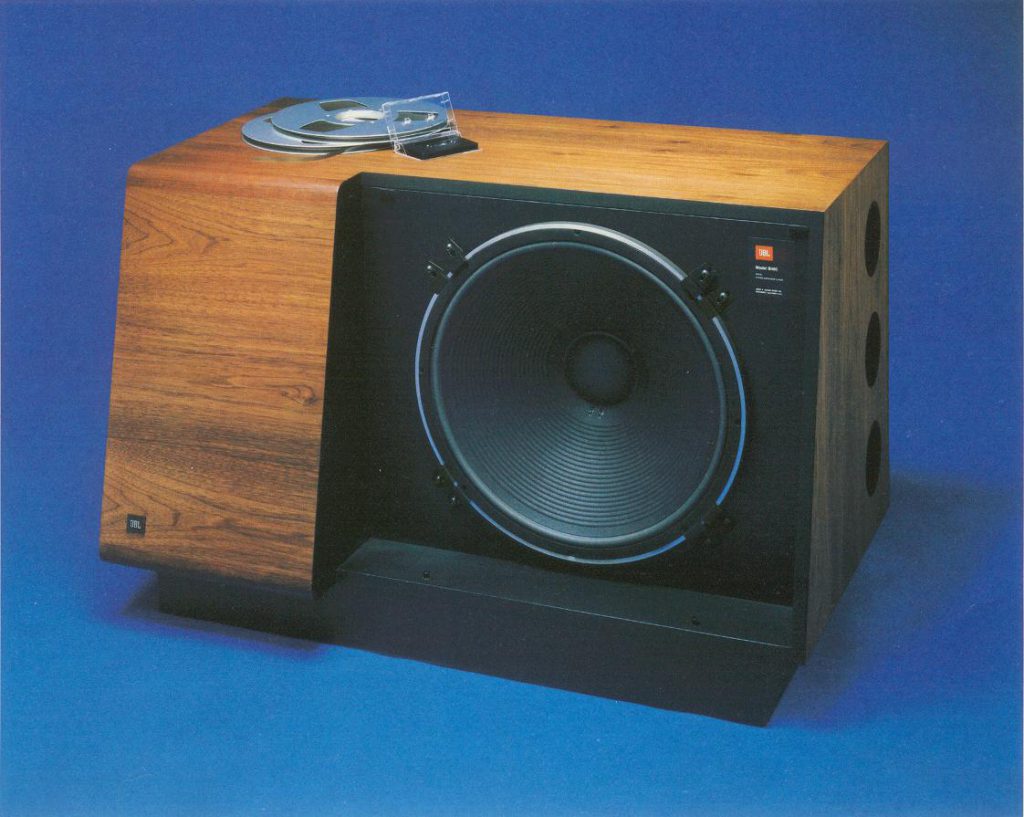

The bass! You’ve been hearing all of the bass, all of the fundamental tones you couldn’t bring home from the concert. It’s not only everything you’ve heard before. It’s also everything you haven’t. The music is rich with sound at the lowest limit of your hearing. And the Ultrabass—the hero of the piece—allows the three-way speakers to be specialists, to concentrate on the top 95 percent of the music. Listen, you’ll hear what that means. Even at a rug-curling, rock-concert loudness, you’ll get a clarity, a smoothness, an enthusiasm for detail you’ve never heard before.

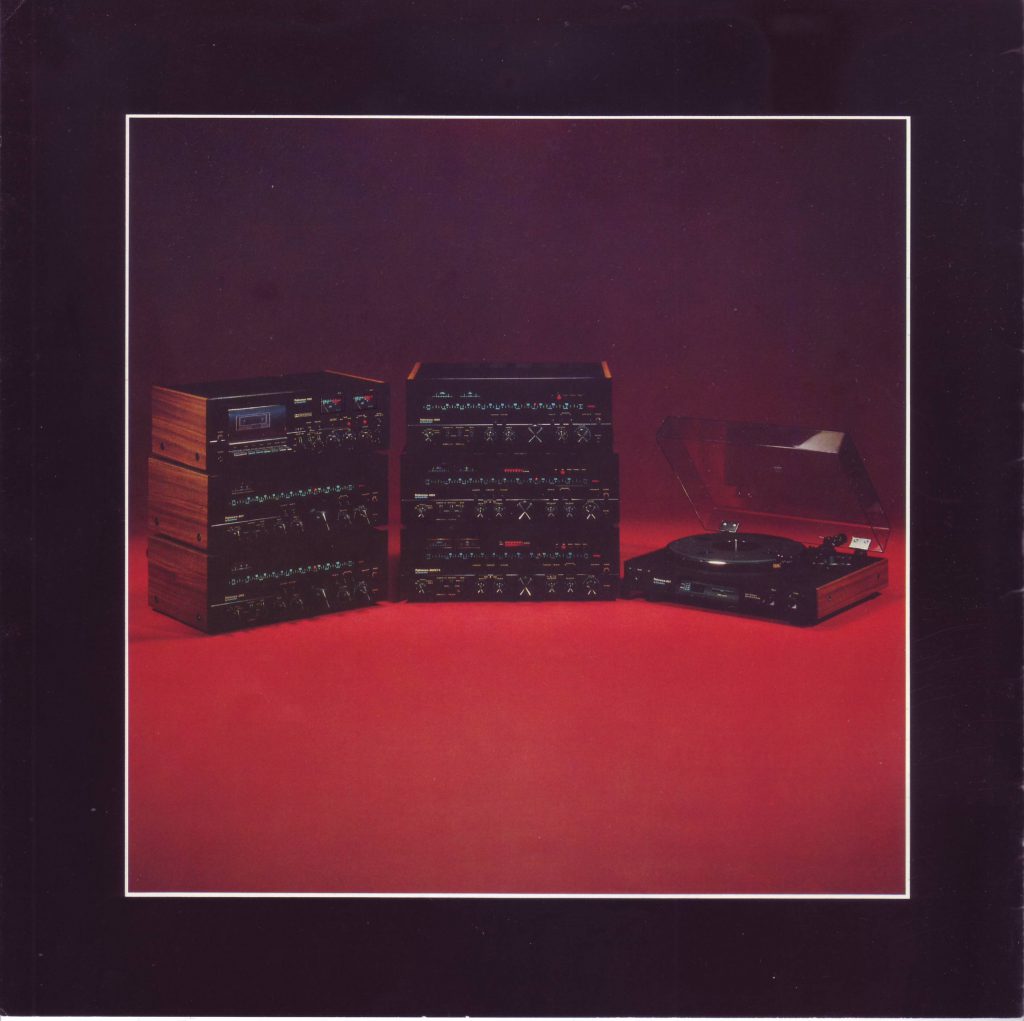

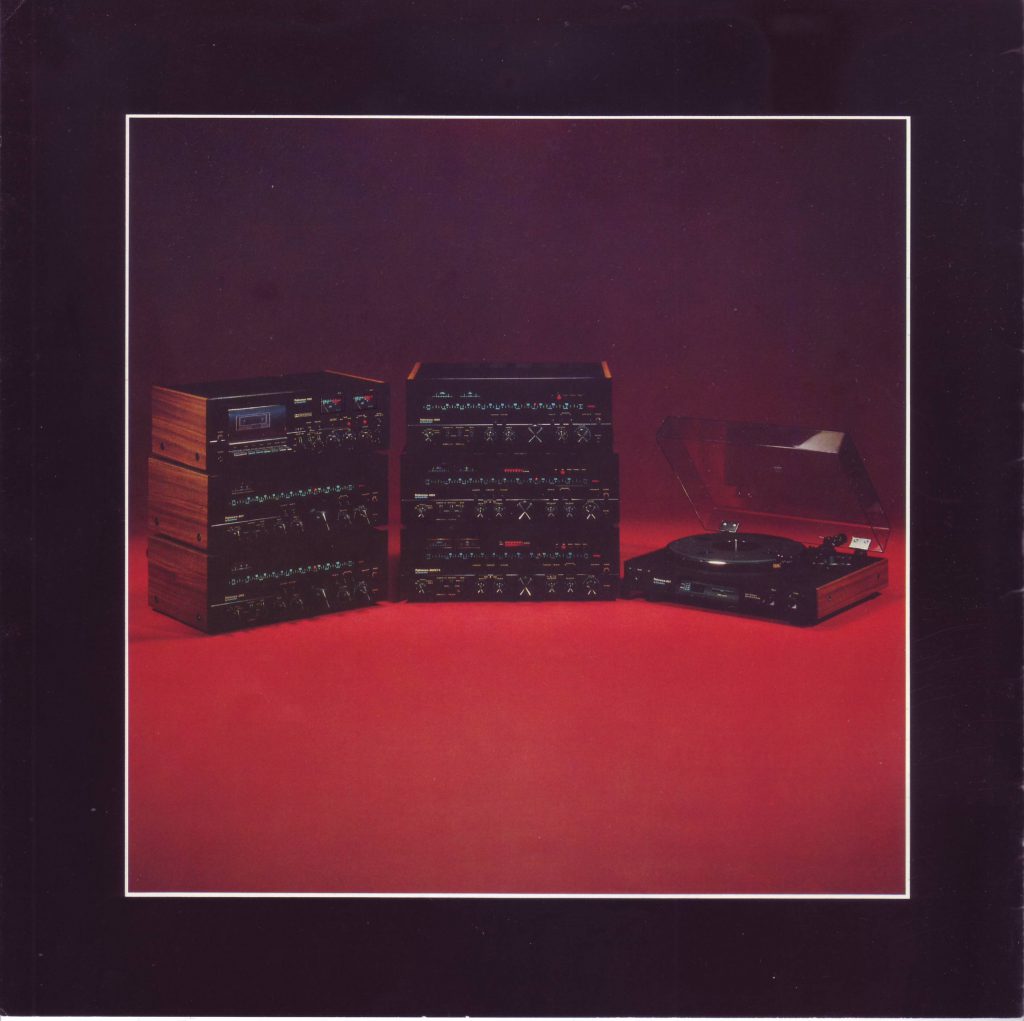

Quadraflex Reference Audio Components Series, 1978

That’s the story. A no-compromise loudspeaker system. You’ve never heard anything like it. Not from us. Not from anyone.

My life as a critical listener began, ironically, with looking at magazine advertisements: JBL, Harman, Marantz, Quadraplex, Epicure Products Incorporated, Optonica. I marveled at the reference systems, which were photographed like diamond necklaces or hundred-thousand-dollar sports cars or revolutionary scientific instruments; I absorbed the language, listened as directed, and shifted my attention from the contents to the qualities of the sound. I clipped out the glossy pages and taped them to my walls: “Changes the Picture of Sound”; “The Realization of the Electrostatic Dream”; “Midnight Dream Components”…. These were single-image fables of life in the land of plenty (never mind the oil crisis or the “malaise” speech or the S&L crisis). For the discerning hippie, banana-yellow enclosures and cherry-red grilles, ergonomic beanbags, spotless shag carpeting, syncretic tribal wallpaper. For the spiritualist, a promise of transcendence and an assembly of components, some winged, superimposed on the outlined figures of a shaman and waterfall. For the tentative futurist, a platoon of Indian-rosewood-veneer cabinets gathered on a tiled platform rimmed with neon and hovering above the clouds. The advertisements promised such accuracy, such fidelity, that you might never miss whatever frequencies were missing; you might rather adjust dials and settings than find the perfect seat in relation to the stage; you might enjoy the stereophonic simulation of cathedrals and clubs as much as the real thing.

I thought I might spend my life chasing down the dream: every waveform seamlessly captured and copied and beamed into living rooms from Tokyo to Los Angeles. But then I realized that there’s a difference between engineering and marketing. In one of my first Audio Engineering Society seminars, the instructor told me about how, in the late 1950s, a psychologist invited a group of college students to enjoy a selection of records on a space-age hi-fi system, only to learn that they preferred their own cut-rate speakers, which, they believed, played music as it was meant to sound. After all, why would twenty-year-olds, infatuated with the experience of becoming themselves, want to trade their sound for one deemed by audio engineers to have a much greater correspondence to reality?

The instructor told me about the efforts that had been made since then to cultivate the desire for realism—perhaps not such an appealing principle for college kids in Cold War America—despite the fact that speakers were not flat and neutral; they were highly manipulative and distorting, full of “personality.” How successful was this program? The instructor grabbed a bundle of issues of Consumer Reports from the late 1970s. He leafed through the pages of speaker reviews, where he’d highlighted phrases that had been taken from advertisements and marketing materials for the same products: clean, undistorted, transparent, sensitive, fidelity.

Around the same time, I began my research into listener preferences—I wanted to make predictions based on real data. As you know, I ended up with a bombshell: if you let people form opinions in the absence of biases—if you hide the speakers behind a curtain and randomly switch between multiple speakers and sounds—then most people will agree on which of the products deserve a ten, for perfection, and a zero, for rubbish. Nobody was more surprised about this than me. I mean, in terms of music and food and beverages and romantic partners, we’re all wildly different, and so everybody thought: you’ve got to pick the loudspeaker that suits you. Turns out that most people, most of the time, choose the same loudspeakers. How about those students who were interviewed by the psychologist? This is a matter of previous experience, which may condition listeners to prefer degraded reproduction: Earbuds, 128kbps, etc. We believe that these biases can be overcome when listeners are subjected to a proper listening test—they end up expressing the same preferences as everyone else.

JBL K2-S9500 speakers, 1990

After I figured this out, my work got easier: I had a reliable database of subjective opinions that I could compare to the technical measurements associated with each component of each product. Eventually, we built an algorithm that predicts which measurements will result in which grades—zero or ten, perfection or rubbish. Of course, Consumer Reports still relies on thirty-year-old criteria and vocabulary that have everything to do with our industry’s realism propaganda campaign, making the reviews irrelevant to what people actually want to hear. And that’s why, today, you see those commercials where polo-shirted men on recliners are levitated, hurtled into the entertainment center and through the flat screen, then deposited, Budweiser bottles still in hand, on the fifty-yard line, facing the offensive linemen, who claw at the turf and snort like wild boars. You’re there. The jerseys are lustrous under the LED floods, like cereal boxes on display in the grocery store, and the applause is thunderous but somehow perfectly balanced, in volume and frequency, with the sugary voices of cheerleaders hopping around on the sidelines. A friend of mine, a designer of custom loudspeakers—he’s always being asked to assess the relationship between the sound coming out of the speakers and the real, live sound—calls this “the geek squad delusion.”

What I’m trying to say is that we’re not after the fantasy of erasing the whole system—never have been. What excites me, personally, is to play records made using analogue equipment, without much pretension or expense, on my precisely calibrated stereo, in a room especially outfitted for the purpose, as indicated by CTA/CEDIA CEB-22, Home Theater Recommended Practice: Audio Design. (You can refer to my personal website for a list of components.) What excites me is the creation of a circuit between the amplified vibration of six guitar strings in a studio however many years ago, the memory of first hearing that power chord in a pool hall or girlfriend’s dorm room or blood-red 1982 Toyota Camry, and the stimulation of my cochlea today by a carefully modulated waveform.

I don’t have such an easy time explaining this to anyone outside the industry, anyone who doesn’t understand that there are massive amounts of math involved, that the output might resemble but can never match the input, that the “average listener” is a complicated and convenient fiction, that we contain as much of these systems as they contain of us—and that this is our accomplishment! Or, this is our accomplishment: hardly anyone ever notices or cares, because quality is high and getting higher.

I mean, I’ve tried, and like I said, hardly anyone ever notices or cares. I was—even my wife, Karen—I was going through this in my mind, cleaning up my apartment, this was many years ago, and she had insisted on coming over to cook dinner, which was surely a ploy to inspect the place, so far kept off-limits. Probably she wanted to find out whether I’m the kind of stunted creature who is so dominated by one impractical fixation as to live in a cocoon of his own filth and unpaid bills and plastic utensils salvaged from take-out orders and so on, which is, really, not quite the case.

She surveyed the listening room, its floor-to-ceiling drawers packed with cables and components. I rambled on about how we inhabit the world of these systems, precisely engineered for us—“us” meaning mathematical models derived from listening tests with a limited number of subjects—and how each technology supersedes what came before, pushing us closer to realism (if not to anything actually real), but in doing so makes us all the more aware of how our memories hinge on the characteristics of cassette tapes played on boomboxes, or 128kbps MP3s played on ten-dollar Altec-Lansing speakers via Gateway PCs with Neolithic sound cards.

JBL B460 subwoofer, 1982

She nodded mechanically, wondering whether to let it drop or forge ahead. Then she asked when it was that people—most people, people like her—stopped noticing or caring about the difference between what’s live and what’s recorded.

Edison, I answered. What do you think the Edison Company’s phonograph advertisements instructed consumers to do? Seek clarity, detail, richness, and tonal balance. Edison packed concert halls and, when the audience had been seated, turned off the lights. (I turned off the lights.) He had a soprano take the stage and sing an aria. (I belted out the first few measures of “O Mio Babbino Caro.”) He had a phonograph play a record of the same aria sung by the same soprano. (I clicked on Callas’s rendition, let her hit the high notes for a few minutes.)

Have you ever actually gone to the opera? she asked.

I had. And I saw what she was getting at: nostalgia, regret, alienation. Sousa, the corruption of the traditional outdoors experience, the decline of storytelling and singing by the campfire and so on. “The ingenious purveyor of canned music is urging the sportsman, on his way to the silent places with gun and rod, tent and canoe, to take with him some disks, cranks, and cogs to sing to him as he sits by the firelight, a thought as unhappy and incongruous as canned salmon by a trout brook.” Welcome to karaoke world, select your preferred filter or format—all that. Click for stadium, click for coffee shop, click for Carnegie Hall.

It’s true: what performs, what is performed, is the system. But I’m a partisan of the system—as if there’s any alternative.

Anyway, like nearly everyone since 1930, Karen had at some point been convinced that the recording is not merely a degraded copy of the performance. We’re still urged by manufacturers to make our own constant comparisons between a rock concert at an arena and a system with a convincing “arena rock” setting. But we now live in a world where the recording is primary; we listen to recordings to recall our experiences of listening to recordings. And, remarkably, this is something we can do, something I, at home, in my listening room, can do: I can activate the memory of hearing the recording for the first time, the combination of formats and equipment and settings that enable me to replay that memory—but also to reconfigure it over time as the memory changes, as I change.

ALEXANDER PROVAN is coeditor of Triple Canopy and a contributing editor of Bidoun. He is the recipient of a 2015 Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant and was a 2013–15 fellow at the Vera List Center for Art and Politics. His writing has appeared in Frieze, Artforum, Bookforum, Art in America, The Nation, and several anthologies and exhibition catalogues. His work as an individual and with Triple Canopy has been exhibited and performed at the 14th Istanbul Biennial: “Saltwater: A Theory of Thought Forms”; Whitney Museum of American Art, in the 2014 Whitney Biennial; the New Museum, as part of “Surround Audience: The Generational Triennial”; Museum Tinguely (Basel); Swiss Institute; the Museum of Modern Art; the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver; MoMA PS1; Artissima 18; and Centro Cultural Montehermoso Kulturunea (Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain).

Commissioning Editors: Laura Herman, Julie Niemi, Anna Gallagher-Ross